Mexico City — Official figures indicate that the number of people considered to be in “multidimensional poverty” decreased by 13.4 million between 2018 and 2024. While this reduction appears to be overestimated in light of household income data reported by Mexico’s National System of National Accounts (SCNM), it is difficult to argue that the number of people in multidimensional poverty did not fall by several million, despite the economy having practically not grown. This is, by all accounts, a commendable and praiseworthy achievement.

Contrary to the expectations of some, this achievement is not fundamentally the result of the federal government’s aggressive increase in spending on social programs, but rather of the rise in remuneration for subordinate work. These wages were, in turn, driven by an increase of more than 100% in the purchasing power of the general minimum wage, which involved nearly tripling its nominal value in just six years, rising from 88 pesos in 2018 to 249 pesos per day in 2024.

Consequently, the minimum wage emerges as the key policy tool behind the significant decrease in poverty that occurred during the administration of President López Obrador. Thanks to work carried out during the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto to replace the minimum wage with the Unit of Measurement and Updating (UMA) as the reference for price adjustments, the current administration found the table set to reverse the repression that had been imposed on the minimum wage for decades.

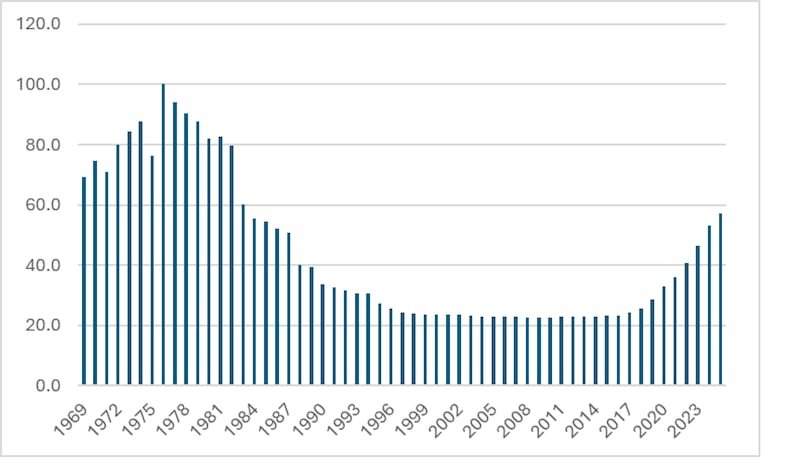

In fact, after reaching its highest value in 1976, the purchasing power of the general minimum wage began a downward trajectory in the second half of the 1970s, which deepened in the 1980s and 1990s. This led to an extensive period of stagnation during which it remained at its lowest levels between 1996 and 2018, a time when the minimum wage was less than a quarter of its 1976 value. Comparing the highest value in 1976 with the lowest in 2009, the purchasing power of the general minimum wage fell by more than 76%.

The process of deterioration of the minimum wage from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s first occurred because it could not keep pace with high inflation rates, which in several years exceeded 100%. Later, it became a “nominal anchor” intended to slow inflation expectations, given that a multitude of prices were automatically connected, through a multiplicity of regulations, to the minimum wages. For many years, the dominant idea among decision-makers at the central bank and the federal government was that avoiding an increase in the purchasing power of the minimum wage was a price that had to be paid to prevent inflation from accelerating. Certainly, this price was paid by formal, low-skilled subordinate employees, but not only by them, as the containment of the minimum also helped repress other wage levels directly above it.

Thus, when considering the last nine complete presidential terms, it is evident that the real value of the general minimum wage only increased during the government of Luis Echeverría (+34.0%), that of Enrique Peña Nieto (+11.7%), and that of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (+108.6%). In the rest of the terms, there were declines: José López Portillo (-20.2%), Miguel de la Madrid (-49.8%), Carlos Salinas and Ernesto Zedillo (-23.4%), Vicente Fox (-2.5%), and Felipe Calderón (-0.8%).

Clearly, the increase recorded during the term of President López Obrador is the most notable and is equivalent to the real value of the minimum wage having increased by 13.0% each year of his administration. This contrasts with the term of President De la Madrid, during which the purchasing value of the minimum wage experienced a dynamic equivalent to a reduction of 10.8% each year.

It is clear that as inflation came under control, stabilizing at average annual levels around 4% starting with the government of Vicente Fox, the rate of deterioration in the purchasing power of the minimum wage decreased and almost halted its downward trend. It then began a timid recovery during the administration of President Peña Nieto, with a global increase equivalent to 1.9% each year, followed by the great utilization of the opportunity with López Obrador. However, this recovery fell short of the historical maximums of the minimum wage, as by the sixth year of his administration, the purchasing power of the minimum wage was barely equivalent to 53% of that in 1976. It is worth mentioning that for the first year of the presidency of Claudia Sheinbaum, 57% of the 1976 minimum wage value was reached.

Despite the strong increases in recent years, it would seem that there is still much room to increase the minimum wage, especially considering that its recovery during the past term was not accompanied by a relevant acceleration of inflation. However, it is important to remember that the minimum wage started from very low levels, even lower than what was paid to low-skilled informal workers, such as domestic workers. Consequently, the strong increases of the past term did not put too much pressure on the cost structure of formal businesses, where the payment of the minimum is more closely monitored.

Nevertheless, as the gap with wages paid in the formal sector narrows, the risk of jeopardizing the viability of businesses increases. This is especially true considering a domestic context of zero per capita economic growth and an adverse and uncertain international environment, given growing protectionism and the manifest unpredictability of our main trading partner.

In this sense, when considering the evolution of the general minimum wage in relation to the “average contribution wage” paid at the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) for all sectors, it is evident that the distance between the two has been shrinking, falling from 25.1% in 2018 to 42.8% in 2024. In the case of sectors with lower average levels of labor skill, the minimum wage comes even closer to the formal market wage, as occurs in agriculture, livestock, hunting, and fishing, and in construction, for which the minimum wage reached 51.9% and 56.6% of the average IMSS wage, respectively, in 2024.

The magic of the minimum wage as a tool for reducing poverty cannot last forever. It would be fantastic to continue reducing poverty through increases in the minimum, but that is not feasible, at least not with the same potency as during the past term. The fact that, until now, increases in the minimum wage have not significantly impacted inflation, unemployment, or the informalization of employment does not mean that this cannot happen if the same growth rate is attempted. The administration of President Sheinbaum appears to be sufficiently aware of this, as reflected by the fact that her first increase, of 12%, is considerably lower than that of any year under her predecessor.

It is desirable for this prudence to continue, because if the government—which, although it has only one of 23 votes on the National Minimum Wage Commission, is the one that ends up setting the direction of its decisions—were to be dominated by a populist reflex, there is a risk of losing much of what was gained in the last seven years.

In this sense, given current conditions, an increase to the general minimum wage in 2026 that is higher than that of 2025 would send a negative signal that would undermine confidence in the economy and increase the probability of ultimately harming those it initially seeks to benefit.

On the other hand, given the political value of the increase and the space that still remains in relation to low-skilled formal wages, it is foreseeable that the increase for 2026 will still be in the double digits, probably somewhere between 10% and 11%. We shall see.

Discover more from Riviera Maya News & Events

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.