Cancún, November 22. The arrest of José Isidro N., leader of the CTM in Quintana Roo, which occurred the day before, overflowed the judicial arena and became the clearest portrait of an unequal struggle: that of a mother against a political-syndical apparatus that for decades operated with impunity and de facto power.

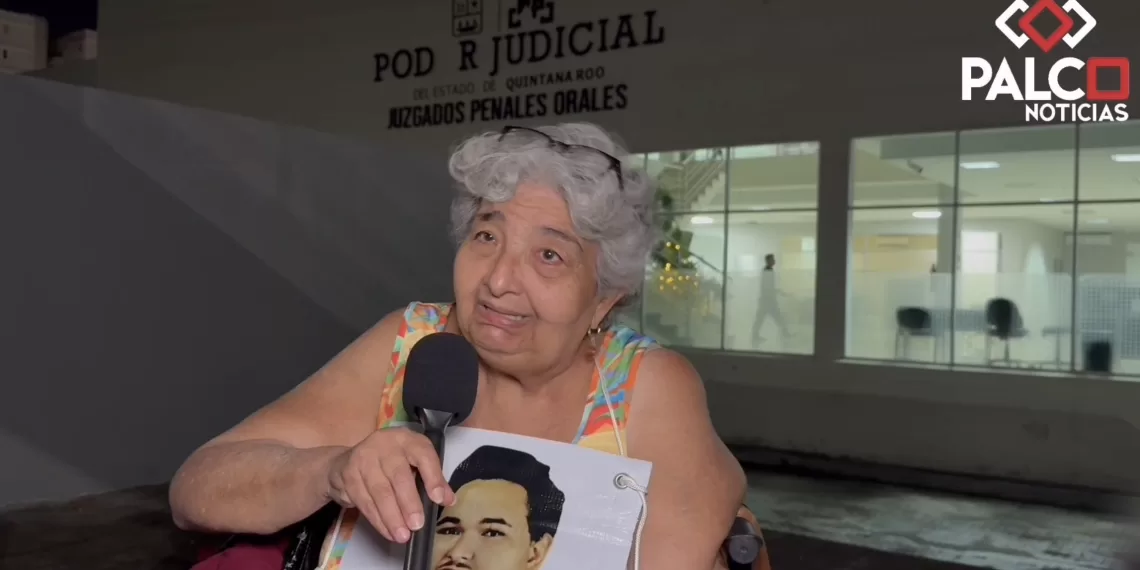

At the center of the story is Carmen Peón Cardín, a woman who not only faces the grief over the murder of her son Luis Fernando Peón in July 2018 but also challenges who can be considered “a political monster” who moved with influences, fears, and silences around him.

“I was afraid, I was terrified, but that fear now gives me courage,” she recalls.

Her phrase synthesizes the deepest battle: that of a citizenry that for years was neutralized by power structures capable of bending entire institutions, and that now begins—still with hesitations—to make its way toward a long-denied justice.

Seven Years That Expose Institutional Deterioration

The story of Carmen is the story of a mother who, from the first day, clashed against the machinery of a justice system anesthetized by political calculations.

Her son, a young man of just 22 years of age, had started his professional internships as a lawyer in the CTM offices, which are very close to his home, in super block 24 of Cancún.

On July 16, 2018, Luis Fernando arrived home and informed his mother that he had been threatened, accused of planning a robbery of money and jewels inside the CTM.

That same day, Carmen relates, José Isidro “N” called her son on the phone and summoned him to his offices. Hours later, he was found tortured and murdered by blows near the Moon Palace hotel complex.

Even so, the investigation remained frozen for seven years.

She recalls that she was never received by prosecutor Miguel Ángel Pech Cen.

“I never had the pleasure of speaking with him,” she says with painful irony. Only deputy prosecutors, secretaries, and public ministries who “pretended to listen” attended her, but they never properly integrated the case file.

With Óscar Montes de Oca, the story repeated: empty meetings, aimless procedures, explanations that never arrived.

“They manipulated everything to their convenience,” she accuses.

“I say it was corruption. And that corruption affected me during all these years.”

The prolonged institutional inaction turned the case into a symbol of the deterioration of the justice system in Quintana Roo, where political interests prevailed over legal duty.

Both prosecutors, Pech Cen and Montes de Oca, were promoted by the then-governor Carlos Joaquín González for the Congress to appoint them.

A Harassed Family While Authorities Looked the Other Way

The details that Carmen narrates reveal an even more disturbing context. Her son never returned after he went to José Isidro’s call.

In the early morning of July 17, armed and hooded men broke into her home looking for the “money and jewels” that supposedly had been stolen from the union leader in his offices.

The family was subdued, they threw everything, and they left without taking anything.

“For a moment I thought they would kill us,” Carmen confesses.

That scene, more typical of organized crime than a union dispute, remained outside the interest of the authorities for years. It was the citizenry—her, her family, and later search collectives—that alone sustained the complaint.

The Power That Brags About Power

For Carmen, facing José Isidro N. was like facing a wall. Not only because of his long tenure in the CTM, but because of the way he himself boasted of his influence.

“The man has bragged about having the means and lawyers to get out quickly from any process,” she relates.

She says it without fear, without trembling: with the serenity of one who learned that the truth is her only shield.

The official narrative of the union leader—who assured that her son had been the “intellectual author” of a robbery within the union—is, for her, an insult in disguise.

“Even conceding the benefit of the doubt, I know who I educated, what values I instilled in him, but if he had done what they say, why didn’t they detain him? Why didn’t they judge him? Why did they send him to be killed? They acted like criminals,” she points out.

Carmen does not tone down. She does not soften. She does not negotiate.

The Breaking Point: Social Pressure That Opened the Doors That Authority Closed

The case only advanced when Mara Lezama arrived in government and a change in the Prosecutor’s Office was promoted, with the appointment of Raciel López Salazar.

At the same time, Carmen found real support in a collective of searching mothers, women who, like her, sustain their lives between pain, memory, and demand.

“We are real cases, very real. And if it weren’t for the group, we would hardly have achieved anything,” she says.

That support allowed her to make her story visible, reactivate the case file, demand reports, reconstruct evidence, and pressure for the arrest warrant to be issued and executed.

What the institutions denied for seven years, organized citizenry obtained, now with officials with better disposition.

The Detention as an Inflection Point

The news of the detention reached her via WhatsApp.

“It’s a cumulus of emotions: you cry, you remember, it hurts… but it also gives you enormous joy because finally a little bit of justice is glimpsed,” she confesses.

For her, the process is just beginning.

She and the searching mothers will remain in a sit-in in front of the oral courts until José Isidro is linked to the process and preventive prison is decreed.

“I don’t expect anything more. I don’t want benefits. I only want what is just to be done,” she affirms.

“Even if it’s one day that he spends in jail, for me it will be a gain, because it will be recognized that he is guilty.”

Toward a Recomposition of the Justice System?

Beyond the individual, the case has become one of the most emblematic in the state.

It exhibits the failure of the past:

- ignored case files,

- complicit or passive prosecutors,

- neglected victims,

- political power operating above the law.

But it also shows a possible new direction:

- a Prosecutor’s Office that reopens files,

- citizen collectives that no longer let go,

- a judicial system forced to make its actions transparent.

Carmen summarizes it with a clarity that dismantles any institutional discourse:

“I only ask that the judges read the case file. That they read it. That they study it. That they don’t sign what others write for them. That they do what corresponds.”

That basic request—that a judge read her file—is the proof of how much has been broken… and of what could begin to be recomposed.

In fact, José Isidro has already been in jail previously. One year after the murder of Luis Fernando Peón, he was detained accused of human trafficking and sexual exploitation, but three years and two months later he went free, thanks to an amparo that was granted to him, due to the case file being poorly integrated in the Prosecutor’s Office.

A Mother Against Power

The case of Carmen Peón Cardín is, today, the story of a mother who exposes the shadows of a system but also the possibility of its reconstruction.

It is the reminder that, when institutions fail, the citizenry pushes; and when the citizenry organizes, even the most entrenched powers can falter.

Her son has been waiting for justice for seven years.

She has been making her way through fear and official indifference for seven years.

And today, for the first time, the balance seems to tilt toward the truth.

Because in the end, this is not the story of a detained union leader.

It is the story of a mother who never gave up.

Discover more from Riviera Maya News & Events

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.